What is Sati Pratha?

Addressing our nation as “Ma tujhe salaam”, we as Indians feel immense pride in being a part of a rich culture that teaches us to respect women, indicated by the very description of India as ‘Ma’ or mother. However, due to lack of knowledge and education, women in India have for a long time in history suffered sizzling injustice. There are instances of female infanticide, Sati practice and honour killings that tarnish the culture of India because of such ignorance.

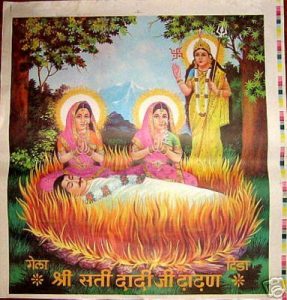

One of the most heinous of injustices that prevailed in our nation was the “Villainous Sati Pratha”. This evil practice forces the widow to immolate herself by sitting atop her deceased husband’s funeral pyre. Sati Practice was also named as “Satidaha” or “Sahagamana”.

Sati goddess is a term used for a chaste woman, who is obedient and devoted. In simple words who is pure like the moon without dark spots. Three abstract principles were manipulated to fuel this social evil of Sati practice. A pativrata or dutiful wife to her husband, a solemn vow to burn by his side at the time of his death, thus as a result bestowed with the status of Sati Mata.

Sati Practice- Drawing from the life of Gods and Goddesses

India’s holy backdrop has instances of true Sati wherein there was no forceful immolation of a widow. The life of Savitri and Satyavan is a perfect example of true love conquering even death. With her wisdom, dedication, modesty, and devotion, Savitri was able to free her husband Satyavan from the clutches of Yama, the God of Death.

Sati Anusuya was offered divine clothes and ornaments from the heaven that would protect her in times of peril, which she later gifted to Goddess Sita during the exile. Sati Ahilya, being innocent and sincere towards her husband, was bestowed Moksha by Lord Vishnu in the incarnation of Lord Rama. These anecdotes and legends that revolve around the many Hindu deities indicate the truth behind ‘Sati practice’.

However, because of illiteracy and deficiency of wisdom, people deliberately started shunning the widows and brutally coercing them to die.

Sati practice History

According to certain reliable records, Sati practice is traced before the period of the Gupta Empire, with its first inscriptional evidence from Nepal. Later, the practice of Sati spread to Madhya Pradesh and then to Rajasthan, eventually becoming an integral part of the culture.

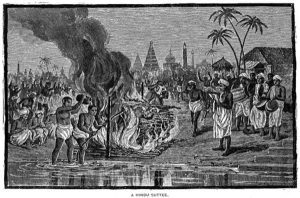

Sati with time gained prevalence in the Chola Empire in South India, and among the Brahmins of Kashmir in the latter half of the first millennium. Most cases occurred in Bengal and Bihar between the 18th and 19th centuries. The Sati Pratha was quite uncommon in the Vijaynagara Empire that covered the state of Mysore and Maharashtra.

Sati Practice- Death rather than surrender

Initially, this ritual was followed only by the Kshatriyas, royal families, and the warrior castes and clans. However, gradually it spread among the other lower castes and communities as well. It is believed that during the Muslim invasions of India, women sacrificing themselves upon the killing of their men became a sign of honour and glory than surrendering their bodies to the greatest of humiliations.

Though the extent to which it was practised is not known with clarity, Sati practice is notably associated with the elite Rajput clans of western India.

What is Sathi Pratha? (Different forms)

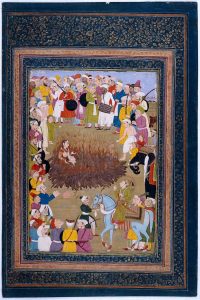

The practise of Sati was carried out in various ways by different communities and in different regions. The most common form was forcing the woman to place herself on her husband’s funeral pyre. In many cases, women would be made to walk or jump into the pyre after it had been lit.

In a few traditions, a small hut was constructed for the widow and her deceased spouse. Several torturous methods were adopted in the past such as a woman could take drugs or get herself snake-bitten so that she is unconscious well before entering the pyre.

Pregnant women, menstruating or those who had very young children were exempted from this heinous norm of sati practice. Women who willingly partook in this ritual were considered to have died chaste and blessed with good karmas for a better life in their next birth. As Brahmins already belonged to the highest caste, there was no karmic rationale considered for them to commit Sati.

Sati History- Rajputs and invasions

A misguided symbol of valour, honour, loyalty, and purity emerged in the form of mass Sati, known as “Jauhar”. This was especially practised by the Rajput queens of Rajasthan when wars were at their peak in the north-western part of India. Special flammable rooms were built in the forts out of combustible materials, wherein women of the royal families collectively burned themselves alive.

Their sense of dignity was way above the mire of enslavement, capture, harassment, and rape. Rani Padmini is known to have performed Jauhar, out of a sense of dignity and truth at the Chittorgarh fort, during the invasions of Alauddin Khilji with raging cries of “Jai Bhavani”.

The evidence of live burials with respect to Sati Practice!

Though widows were buried in some European regions, a Flemish painter Frans Balthazar Solvyns is believed to have witnessed an Indian Sati involving burial. The barbaric custom included the woman shaving her head, as the celebration went on around her.

In some communities, a widow was made to lie down next to her dead husband. And they conducted some parts of both the marriage and the funeral ceremonies before she was burnt alive.

The myriad traditions behind the Sati practice

A tradition developed in which Jivit (living sati) was seen as virtuous around the twentieth century. A jivit is a woman who once wished to commit suicide but later gives up her desire to die. Two famous jivits were Bala Satimata and Umca Satimata, surviving until the early 1990s.

Ancient customs depict Sati practice as – closure to marriage. It was a voluntary act on the part of a dutiful wife who showed her greatest devotion and love to her better half. The woman, who desirably chose sati usually wore extravagant dresses, decked in jewellery as if her marriage before sighing goodbye to her friends and relatives.

However, with the passage of time as depraved thinking became dominant, the women were pressurized to accept Sati as an honour. A widow was considered as a burden and ominous with no role in society. Also, the relatives didn’t wish to share the family property with the woman as greed allured their minds.

Certain cruel measures were taken to prevent a widow from escaping once the flames rose towards the clouds; such as their feet were tied to the posts fixed to the ground or to one of the pillars. Drugs were often used to sedate the widow so that while she was being taken, there is no such struggle.

If we examine the history of Sati in India, the most inhuman ones were those in which relatives and family members kept pushing the unwilling widow to the hottest part of the fire. Women did express immense guilt, sorrow, love, or affection but it is ridiculous to think that women consented to the practice of Sati.

What fuelled the practice of Sati?

Certain theories that were used to back this practice were:-

Sati practise was believed to have been supported by scriptures.

Unscrupulous neighbours sought to annex the dead man’s property from his surviving wife who would be the inheritor, if alive.

It was a means of escape for a woman with no hope of survival in the abysmal conditions of poverty and misery. Especially those who were childless or old and had lost their only personal support.

Widow Remarriage wasn’t a common practice and not so favoured.

Sometimes, in the past, the legend of Goddess Sati and Lord Shiva was manipulated to validate this utterly inhuman practice. As per the mythological epic, the father of Goddess Sati invited all the deities and kings except Lord Shiva to a massive Yagna.

Thus, raged by his humiliation, Sati immolated herself in the fire of the yagna. Consequently, her rage was transferred to Lord Shiva who with a gigantic throb began the dance of destruction. Hence, this has nothing to do with a widow committing suicide. But it’s about a married woman’s anger, frustration, and sense of self-respect for her life partner.

Misinterpretation of the Vedas and Sanathan Dharma

Sati is nowhere mentioned in Dharmasutras, Grhysutras, or in Brahmanism and early Dharmashastra literature. There are some Vedic mantras which were misinterpreted in the medieval age by some ignorant priests- believed to support the practice of Sati.

The correct interpretations are:-

Atharvaveda 18.3.1

This Woman has chosen her Husband’s world earlier. Today she is sitting beside your dead body. Now bestow upon here both wealth and offspring for rest of her life to continue her afterlife in this world. Thus, this mantra speaks about the continuation of worldly affairs by Women in this world after her husband’s death.

The same advice is attested in Atharvaveda 18.3.2

Rise, come unto the world of life, O woman: come, he is lifeless

by whose side thou liest.

Wifehood with this thy husband was thy portion who took thy

hand and wooed thee as a lover.

A famous passage from Rigveda 10.18.8 addresses the widow and says: – Rise up, abandon this dead man, and re-join the living. It explicitly states that the widow should now return to her normal life.

The fraud related to the interpretation of Rigveda 10.18.7 is said to have been exposed by Maxmuller.

In this mantra, a widow is advised to go ahead (Agre) in her life rather than go in funeral pyre after her husband’s death. The word Agre was misinterpreted as Agni (fire).

Satapatha Brahmana explains that ‘One should not depart before one’s natural lifespan’- suicide by anyone is against the law of nature.

What the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata have to say regarding the practice of Sati?

Madri, the second wife of Pandu, burned herself to death after her husband died. She considered herself responsible for his death as she could not save her husband from the poison of the curse. Her sacrifice was not the result of any Sati Pratha but, sheer love for her husband. But no women, in Mahabharat, are known to have sanctioned Sati whose husbands were killed in the eighteen-day long war.

There is no conclusive evidence of the Sati practice. Though the widows of Ravana and his sons did proclaim their desire to die, unable to bear the bereavement. All of them remained alive and two of them even remarried.

Parashara Smriti says that a widow or a married woman whose husband has left her for good, can remarry if she so decides.

Who abolished Sathi Pratha?

In the 16th century, Humayun was the first to try a royal agreement against the Sati practice, followed by Akbar.

It was Raja Ram Mohan Roy, a reformer, who took the first sincere step for the abolition of Sati Practice in India with the help of the British Government. A Christian evangelist, William Carey also supported the opposition to this barbaric practice. The Governor-General of India – Lord William Bentinck declared the Bengal Sati Regulation on 4th December 1829. Henceforth, Sati in India today is punishable by law.

The Sati Act

The horrendous case of 18-year-old Roop Kanwar, of Deorala district in Rajasthan, triggered the state and later the nation to expand the legislation against the practice of Sati. Though Roop Kanwar’s identity acquired the status of a deity (Rani Sati or Satimata) and people began venerating her; the Indian Government came up with The Prevention of Sati Act.

Thus, making it illegal and punishable to aid or glorify the practise of Sati. The abolition of sati was only the first step in this venture. Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar initiated attempts for widow remarriage which gained wide acceptance after the changes brought about by Aryasamaj. There were a few shocking cases in-between the years 2003- 2008. The situation has improved significantly compared to the bygone 19th century. Thanks to the activists and the relentless pioneers of woman’s rights like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, the number of recent sati cases in India has declined significantly.

Conclusion

In our revered Sanathan Dharma, women have always been portrayed with dignity, and wives seen as next to god. The sanātana-vaidika-dharma has always been friendly to men and women equally. Assuming different roles does not mean inequality. In ancient India, people enjoyed equal rights whether they were men or women.

There was no such trend for rapes; there is no support for molestation in our scriptures. Countless invaders have suppressed our culture. Often concluding it as savage but it is not the fault of the Vedas, nor the great Acharyas. But, our rigid ignorance of the Shastras, Upanishads and the Sutras. The history of sati practice was a consequence of that.

It is the duty of women themselves that along with having Goddess Sita as their role model. They must become empowered like Draupadi doing all her rightful duties. She should also develop the strength of the heart like the two goddesses. bold enough to take a stand when appropriate.

Comments